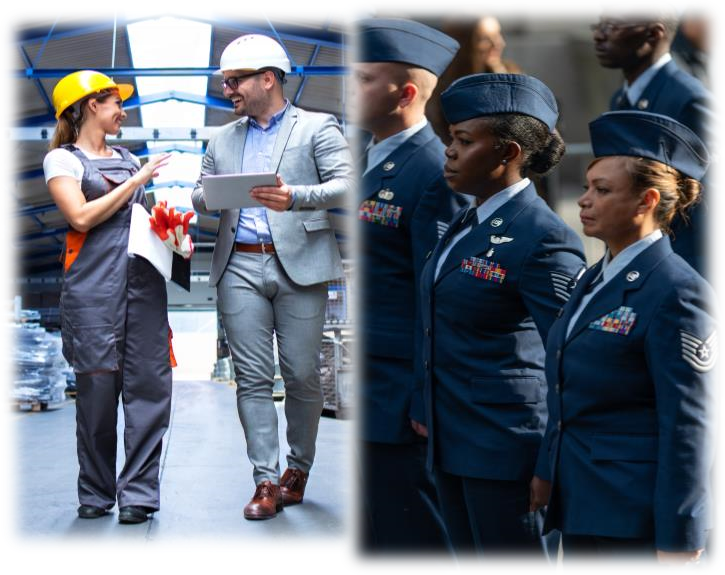

A good leader doesn’t have to bark orders to get good work from their team.

There was a time when more than half business executives had previous military service. Broadly speaking, that was good news for their companies. A study by the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University found that in 1980 59% of the CEOs of large, publicly held corporations had served in the military. By 2013 that number had dropped to 6.2%. Kellog’s study also found that firms run by CEOs with military experience perform better than their non-veteran counterparts. [1]

This significant decline in veteran-led companies means that when we talk about using leadership principals of the armed services, all too many people turn to Hollywood instead of personal experience to envision that military leadership. How many scenes have you watched where a superior officer loudly dresses down a subordinate in order to spur him into action? It might make for good drama, but, in our experience, it doesn’t have much to do with reality. General Colin Powell, looking back on a military career that took him all the way to chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, says he doesn’t remember ever having to use the phrase, “That’s an order” while in uniform. Good leaders know how to clearly communicate their vision to the troops: the stakeholders, partners, colleagues and employees. It’s the key to creating a motivational climate where everyone is “on board” and passionately rowing in the same direction.

Cracking the whip yields only short-term results and even children often get resentful when the only reason for doing something is, “Because I said so.” The days of command-and-control leadership are over!

All the way back in 1879, General John Schofield told the graduating class at West Point that, “The discipline which makes the soldiers of a free country reliable in battle is not to be gained by harsh or tyrannical treatment. On the contrary, such treatment is far more likely to destroy than to make an army. It is possible to impart instruction and give commands in such a manner and such a tone of voice as to inspire in the soldier no feeling, but an intense desire to obey, while the opposite manner and tone of voice cannot fail to excite strong resentment and a desire to disobey. The one mode or other of dealing with subordinates springs from a corresponding spirit in the breast of the commander. He who feels the respect which is due to others cannot fail to inspire in them respect for himself. While he who feels, and hence manifests, disrespect towards others, especially his subordinates, cannot fail to inspire hatred against himself.”

Unfortunately, some executives still think that leadership means barking orders, and many a frontline supervisor is fond of fear, sarcasm and ridicule as the motivational tools of choice. Maybe that’s the environment they saw as they came up through the company and so they emulate the only model they know. If you want your organization to sustain peak performance, you must break that cycle.

The world is different than it was in 1879 or even 1980. To achieve long-term sustainable growth, your organization needs leadership with skills like good communication, creativity, collaboration and the ability to create motivational climate.

No one knows more about leadership, strategy, discipline and creative thinking than the U.S. military’s commissioned and non-commissioned officers. That’s largely because the armed forces make a point of providing solid leadership training that starts very early in the lives of each Soldier, Sailor, Airman and Marine. Civilian companies would benefit from the same approach. Successful companies realize that successful leadership requires a new skill set.

What are you doing to ensure your supervisors and managers develop that skill set?

[1] https://www.kellogg.northwestern.edu/faculty/benmelech/html/BenmelechPapers/MilitaryCEOs.pdf